Research Article / Open Access

2020; 3(6): 357– 364 doi: 10.31488/HEPH.157

Citizens, Neighbors, and Informal Caregivers Exposed to Challenging Behaviors and Behavioral Changes in Community-Dwelling Older Adultswith Cognitive Impairment:A Review

Elodie Perruchoud*1, Armin von Gunten*2, Tiago Ferreira*2, Alcina Matos Queiros*3,Henk Verloo*4

1.School of Health Sciences, HES-SO Valais and Department of Nursing Sciences,University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Switzerland

2.Department of Psychiatry, Service of Old Age Psychiatry, Lausanne University, Prilly-Lausanne, CH-1008, Switzerland

3.Geriatrics and Old Age Psychiatry, Health and Social Services Department, Directorate-General for Social Cohesion Bâtiment Administratif de la Pontaise, Switzerland

*Corresponding author: Elodie Perruchoud: School of Health Sciences, HES-SO Valaisand Department of Nursing Sciences,University of Applied Sciences and Arts,Western Switzerland, 5, Chemin del’Agasse, Sion CH-1950, Switzerland; Tel: +41 58 606 86 78.

Abstract

Background:Many community-dwelling older adults(CDOAs) experiencing a noticeable decline in cognitive ability may have mild cognitive impairment (MCI).It is important for health-care providers working in dementia care and public health policy to understand local environments, including neighborhoods, because older adults move between their own homes, friends’ homes, family members’ homes, shops, and various formal care environments. Little is known about how much citizens and neighbors support CDOAs, such as by alerting health-care professionals about needs for further support to optimize their health, safety, and quality of life at home.Aims:This review sought to identify and analyze publications examining the barriers to and facilitators of the detection and handling of behavioral problems in CDOAs with probable MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia (as recognized by citizens, neighbors, and informal caregivers) and how health-care systems deal with them.Methods: Existing publications weresearched forin sevenelectronic databases with no date limitations, from their inception until October 31, 2020.An additional search was conducted in Google Scholar.Results:3’810 records of all sorts, publication dates, and languages were identified. Only two studies were retained for review.Analysis of the literature failed to identify the profiles of the citizens, neighbors, and informal caregivers who are among the first in the community to be exposed to older adults’ behavioral problems. Conclusion: No studies to date seem to have explored how citizens, neighbors, and non-family informal caregivers are exposed to and deal with the behavioral problems presented by CDOAs. Because older adults living alone in their own homes are frequently quite isolated, community life can become a determining factor in the process of detecting and orienting older adults presenting with MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia. As a result, it seems necessary and urgent to promote research in this field.

Keywords:Mild cognitive impairment, community-dwelling older adults, behavioral problems, local environments, detection, referral

Introduction and Background

The increasing number of cognitively impaired older adults living in their own homesis a rapidly growing, global public health problem[1]. Worldwide, there are currently more than 50 million people withmild/moderate/major neurocognitive disorders (diagnosed and undiagnosed dementia). Every year, there are nearly 10 million new cases[2].The total number of people with dementia is projected to reach 82 million in 2030 and 152 million in 2050[3]. The relationship between aging and dementia has been well demonstrated[4].The detection of early symptoms of cognitive impairment among older adult populations is recommended as early as possible[5].

Several definitions and classifications have been applied to early cognitive impairment over the years. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is currently the most commonly used concept and term [6,7].Thus, thisreview uses the term MCI and focuses on MCI, the progression from MCI to dementia, and on dementia.

Manycommunity-dwelling older adults(CDOAs) who can still carry out their activities of daily living but present with a noticeable decline in cognitive ability may have MCI[8].MCI is classified into amnestic and non-amnestic types, which each have two subtypes: single domain and multiple domain[9]. In amnestic MCI the memory loss is the predominant symptom and is associated with a high risk of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease[10].Individuals with non-amnestic MCI have impairments in domains other than memory(language or executive function, disturbances of attention/concentration, information processing and psychomotor speed) and have a higher risk of conversion to other forms of dementia, such as diffuse Lewy body dementia[11]. Multiple-domain MCI denotes a greater extent of disease than single domain MCI and is more frequent[12-14]. Amnestic MCI is about twice as common asnon-amnestic MCI [15].Prevalence estimates for MCI amongCDOAs are as high as 22% for those aged 71 years and older, with prevalence among older adults cared for in memory clinics estimated at nearly 40%[16].Progression to any form of dementiamay occur at a rate 3 to 5 times higher among older adults with MCI than amongthose with normal cognition,which itself progresses at an annual rate of 12% in the general population and up to 20% in high-risk populations [6]. As a transitional stage of early cognitive impairment, much attention has focused on identifying modifiable and unmodifiable risk factors to prevent or delay the progression from MCI to dementia.The early detection of MCI among CDOAs could be a crucial factor inhelping them to remain in their own homesfor as long as possible, and this would require follow-up treatment and care for the underlying causes of their behavioral changes and optimal referral to health-care professionals[17].

Most people with MCI live in the community with family; however, a significant proportion lives at home alone[18]. Given the typicallyprogressive nature of cognitive impairment-the hallmark of MCI and mild dementia-older adults livingin the community face many challenges, whether they livealone or with their family.Living in the community can be beneficial for people with MCI because some will probably have to cope with their deteriorating cognitive function alone at home[19].Behavioral and psychological symptoms(BPS)may occur in MCI as wellas any form of dementia[18-20]. The onset and clinical manifestations of the BPS associated with MCI and dementia areheterogeneous: they can be affective, psychotic, or behavioral[21, 22]. Affective BPS referto anxiety, depression, emotionalism, irritability, or elation; psychotic BPS refer to delusions, hallucinations, and misidentification syndromes; and behavioral BPS refer to aggressiveness, eating disorders, agitation, wandering, and hoarding. BPS are among the most harmful features of dementia and reach a five-year prevalence above 90%[21]. BPS also lead to individual suffering and dramatically increase caregiver burden for both health-care professionals and informal caregivers. They are thus often a reason for institutionalization[23].The etiopathogenesis of BPS is complex, with numerous biological triggers interacting with psychological stress, personal predisposition, and social aspects such as living environment[24-26].The various combinations of these cognitive changes makeliving independently complicated and risky[27].Diagnosing cognitive impairment is less likely among CDOAs although dementia-related memory loss and behavior can significantly affect their independence [28, 29].

Local environments, including neighborhoods,areimportant to know for health-care providers working in dementia care and public health policy because older adults move between their own homes, friends’homes, family members’homes, shops, and various formal care environments.Neighborhood supportis often considered crucial for enabling people to remain independent and active as they age[30, 31]. The early detection of behavioral changes among CDOAs,secondary to acute onset delirium or to BPS, is an essential determinant of rapid care enabling the elderly to remain at home [32,33].

Numerous studies highlighthowindividuals with dementia strive not to make mistakes to avoid being placed in a nursing home[34, 35].Others change their routines to minimize the risks associated with cooking and cleaning theirhomes[18, 36]. The desire to keep cognitive impairment hidden increases the difficulty of identifying those who can no longer copeindependently[18, 37]. Secrecy raises the risks of some patients becoming invisible within their community, a subgroup hidden from their fellow citizens. Some older adults have limited or no support and are more likely to be isolated from formal sources of support, including health-care[37]. As a result, friends and neighbors often become informal caregivers.Thus, they are the first to recognize the onset of behavioral changes. Home health-care services staff may not be aware of changes or may miss any deterioration in the health of the people they visit[38, 39].

Little is known about how much citizens and neighbors support CDOAs, such as by alerting health-care professionals for further support to optimize their health, safety, and quality of life at home[40]. One study found that outcome-focused care interventions improved the subjective well-being of people with dementialiving alone [18, 41, 42]. Outcome-focused services were those that met the goals, aspirations, or priorities of the older adults using those services. However, optimizing health and providing care interventions for people with dementia are complex activities. Although there is extensive information about home-based dementia care, information about the implementation of care in situations where older adults are living alone is still limited[43]. Therefore, our reviewseeks to identify the challenges facing older adults withMCIor mild-to-moderate dementiawho live alone and to explore some of the practical implications for community dementia care.

Aims and Objectives of the Review

This review sought to identify and analyze publications examining the barriers to and facilitators of the detection and handling of behavioral problems in CDOAs with probable MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia, asrecognizedby citizens, neighbors, and informal caregivers and how the health-care system deals with them.

Research questions

• Which citizens, neighbors, and informal caregiversreport on CDOAs’ challenging behaviors?

• Do they report on CDOAs’abnormal behaviors or behavioral changes?

• What kind of information do they report?

• To whomdo they report the presence of abnormal behavior or behavioral change?

Methods

Design

An overview of existing publications was conducted. The following components guided the review:populations, concepts, and the contexts of the documentary search(44).

Populations

• Cognitively impaired community-dwelling older adults (CDOAs)

• Patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or mild-to-moderate dementia

• Informal caregivers, citizens, neighbors, emergency responders, administrative personnel, workers, policy makers

Concepts

• Behavioral changes, abnormal behaviors, challenging behaviors

• Behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPS)

Contexts

• Older adults living in the community

• Living in an apartment or house, with or without support from social and health-care services

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| • Community context | • Intra-hospital or institutional context (homes, protected apartments, nursing homes) |

| • Adults aged 65 years or more | |

| • Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or mild-to-moderate dementia | |

| • Behavioral and psychological symptoms and signs (BPS) |

Outcomes of interest

• Profiles of the individuals reporting older adults’ challenging behaviors

• Barriers to and facilitatorsof the detection and handling of behavioral problems in older adults,as expressed by citizens, neighbors, and informal caregivers,and how health-care systems deal with them

• Difficulties and needs expressed by the reporters

• Information channels used for dealing with an older adult with cognitive or behavioral problems

• Interventions and added value

• Recommendations for research,training, and practice

Literature Search Strategy

We conducted a review of published articles in the following electronic databases, from their inception until October31, 2020: PubMed (from 1996), Web of Science Core Collection (WOS) (from 1900), the Francophone Public Health Database (Banque de données francophone en santé publique, BDSP) (from 1993 to 2019), the PASCAL and FRANCIS bibliographic databases (from 1972 to 2015), SocINDEX – EBSCO (from 1895), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I (from 1939) and DART-Europe E-theses Portal (from 2005). An additional search was conducted in Google Scholar.

Types of publications

Quantitative and qualitative publications, mixed-methods studies, editorials, letters to editors, congress abstracts.

Language

No restriction.

Period

No restriction.

Concept keywords

| Concepts | Synonyms |

|---|---|

| • family caregiver | • Emergency responders, administrative personnel, workers, citizens, neighbors, policy makers |

| • Cognitively impaired community-dwelling older adults | • Dementia, mild cognitive impairment, behavioral and psychological symptoms and signs (BPS),changing behavior,challenging behavior, abnormal behavior,mental disorders, cognitive defects, neurocognitive disorders |

| • Community | • Public health, community health, neighborhood |

Search equation

The subject headings and keywords (title/abstract) used in the search equations in the different databases are described in the annex.

Results

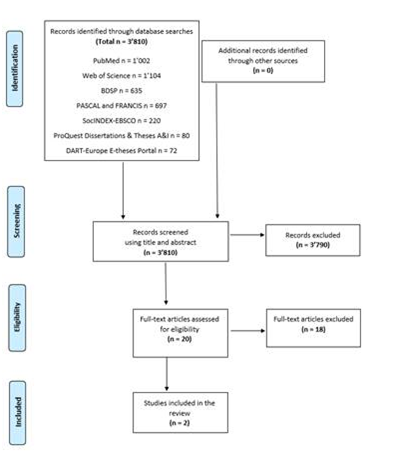

A total of 3,810 potentially relevant records were identified through our database literature search carried out between October 9 and October 21, 2020. After screening the records by examining their titles and abstracts, 3,790 were excluded, and 20 studies were retained to be read in their entirety. In the end, only 2 studies met our search criteria and were retained for review (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow chart summarizing the results of the research strategy, based on the recommendations of the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (2018) (45).

However, our analysis of existing literature failed to identify the profiles of the citizens, neighbors, and informal caregivers who are among the first in the community to be exposed to older adults’ behavioral problems. It also proved impossible to identify the factors hindering or facilitating these people when they are trying to detect symptoms, manage disorders, and orient CDOAs presenting with MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia. Finally, the difficulties and needs expressed by these community actors in such situations, the intervention strategies that can be put in place to help them, as well as which information channels could or should be used to orient CDOAs through health-care systems have yet to be explored.

The two selected studies did give some useful insights. The transversal descriptive survey by Streams et al. (46), carried out in 2003 in Kentucky (USA), aimed to examine the incidents that caused informal caregivers (n = 416) to ask for a diagnostic assessment of their family member in a memory clinic. They managed to identify 903 different incidents that were suggestive of potential problems. The survey also aimed to identify the caregivers who first suggested those assessments.

Almost half of the informal caregivers who identified specific changes in the older adults in their care underlined that there was a combination of incidents rather than just one. Indeed, 85% of informal caregivers identified at least one cognitive change, whereas 40% identified at least one personality or behavioral change. Among cognitive disorders, memory loss was the most frequently noted trigger incident (45% of cognitive changes), followed by disorientation (11%). Among personality and behavioral changes, the most frequently noted trigger incidents were symptoms of depression (12%), violence and attitude problems (11%), a lack of personal initiative (11%), paranoia and delirium (11%), and a drop-off in personal hygiene and cleanliness (11%). The study found that it was family caregivers themselves (35%) who most frequently oriented older adults towards memory care practices, followed by attending physicians (31%), other family members (19%), specialist physicians (10%), non-physician health-care professionals (4%), and other people neither family nor involved in health-care (4%). In only 3% of cases, it was the older adults themselves. It is interesting to note that cognitive disorders were more frequently identified by others than behavioral changes and that 4% of cases were reported by people who were neither a family member nor a health-care professional.

The qualitative study by Peterson et al. (47), carried out in 2016 in California (USA), aimed to understand the family caregivers’ perspectives (N = 27) by using semi-structured interviews about the trigger incidents, which caused them to seek out more information, the obstacles they encountered, their training needs, and their preferences with regards to information channels. Seventeen of those family caregivers had difficulties identifying a specific trigger incident. They reported that they became increasingly conscious that something “wasn’t quite right” and that this prompted them to seek out more information and ask for a medical assessment. For the nine other family caregivers, the trigger incidents were memory loss, cognitive decline, problematic behavioral symptoms, or diminished functional capacity. The difficulties in finding pertinent information frequently resulted in a lack of knowledge about what they were dealing with rather than any reticence to take on the role of family caregiver. The majority of family caregivers reported having enough information at their disposal. They were prepared to use numerous sources of information (printed documentation, internet and community resources, and speaking to health-care professionals). However, most family caregivers insisted on the importance of their information channels being valid and reliable sources, notably, being recommended by an attending physician. This study revealed several interesting issues because it recommended that community-based training programs be organized to help family caregivers identify and describe the various cognitive, functional, and behavioral symptoms they encounter at an early stage.

Although these two papers present findings and recommendations for the family caregivers of older adults presenting with MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia, we conclude that their diverse elements could be transferred to other key actors in the community (citizens, neighbors, informal caregivers).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our analysis of the existing literature identified no studies that fully matched or addressed particular our field of interest. The only two studies coming close to our research aim enabled only a partial identification of the key civil society actors who are the first to be exposed to incidents suggestive of MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia in a CDOA. Both the studies selected dealt mainly with close family caregivers. To the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have explored how citizens, neighbors, and non-family informal caregivers are exposed to and deal with the behavioral problems presented by CDOAs. However, because older adults living alone in their own homes are frequently quite isolated, community life can become a determining factor in the process of detecting and orienting older adults presenting with MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia. The early identification of behavioral problems helps to ensure a rapid initiation of care. Early treatment management enables not only effective treatment of the underlying causes of these changes by health-care professionals but also the possibility of home care and fewer of the unnecessary hospitalizations that can be harmful to the older adult and to health-care system budgets. As a result, it seems necessary and urgent to promote research in this field and a search for health-care promotion strategies that raise awareness of the issues at stake.

In order to identify the key civil society actors who are among the first to recognize MCI or mild-to-moderate dementia through their interactions with CDOAs, it will be necessary to carry out exploratory, longitudinal studies on this topic. Public health authorities will subsequently be able to develop intervention strategies based on these studies. It is essential to be able to identify the difficulties and needs described by the key actors in society who are among the first to detect symptoms, manage treatments, and orient CDOAs with behavioral problems along the right pathways. This will help to develop public education or training initiatives to improve the public’s knowledge and capacity to respond. Finally, the ability of key societal actors to detect and respond early enough to CDOAs’ could have a positive effect on professional health-care responses, through the fast, efficient implementation of optimal care. This will favor more home care for older adults, lead to fewer hospitalizations or institutionalizations, and reduce the number of unnecessary interventions, thus saving on health-care costs.

Conflicts Of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

ANNEX

Search equations

| Database | Equation |

| PubMed | ("Aged"[Mesh] OR elder*[tiab] OR eldest[tiab] OR "old age*"[tiab] OR "older people"[tiab] OR "older subject*"[tiab] OR "older age*"[tiab] OR "older adult*"[tiab] OR "older man"[tiab] OR "older men"[tiab] OR "older woman"[tiab] OR "older women"[tiab] OR "older population*"[tiab] OR "older person*"[tiab] OR aging[tiab] OR ageing[tiab] OR senior*[tiab] OR "late life"[tiab] OR "oldest old*"[tiab] OR "very old*"[tiab]) AND ("Cognitive Dysfunction"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "Memory Disorders"[Mesh] OR "Cognition Disorders"[Mesh] OR "cognitive impair*"[tiab] OR "cognitive decline*"[tiab] OR "cognitive loss"[tiab] OR "memory disorder*"[tiab] OR "memory loss"[tiab] OR "Cognitive Dysfunction*"[tiab] OR "Mild Neurocognitive Disorder*"[tiab] OR "Mental Deterioration*"[tiab] OR "cognition disorder*"[tiab] OR "cognitive change*"[tiab]) AND ("Social Behavior Disorders"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "behavior disorder*"[tiab] OR "behaviour disorder*"[tiab] OR "behavioral disorder*"[tiab] OR "behavioural disorder*"[tiab] OR "challenging behav*"[tiab] OR "behavioural change*"[tiab] OR "behavioral change*"[tiab] OR "behavior change*"[tiab] OR "behaviour change*"[tiab]) |

| Web of Science | TS=((elder* OR eldest OR "old age*" OR "older people" OR "older subject*" OR "older age*" OR "older adult*" OR "older man" OR "older men" OR "older woman" OR "older women" OR "older population*" OR "older person*" OR aging OR ageing OR senior* OR "late life" OR "oldest old*" OR "very old*") AND ("cognitive impair*" OR "cognitive decline*" OR "cognitive loss" OR "memory disorder*" OR "memory loss" OR "Cognitive Dysfunction*" OR "Mild Neurocognitive Disorder*" OR "Mental Deterioration*" OR "cognition disorder*" OR "cognitive change*") AND ("behavior disorder*" OR "behaviour disorder*" OR "behavioral disorder*" OR "behavioural disorder*" OR "challenging behav*" OR "behavioural change*" OR "behavioral change*" OR "behavior change*" OR "behaviour change*")) |

| BDSP |

|

| PASCAL and FRANCIS database |

|

| SocINDEX-EBSCO |

|

| ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I |

|

| DART-Europe E-theses Portal |

|

We eagerly await your response.

Abbreviations

MCI: mild cognitive impairment; CDOAs: community-dwelling older adults; BPS: behavioral and psychological symptoms.

References

1.Ponjoan A, Garre-Olmo J, Blanch J, et al. Epidemiology of dementia: prevalence and incidence estimates using validated electronic health records from primary care. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:217-28.

2.(WHO) WHO. Dementia: Key facts 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

3.Organization WH. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide. Geneva; 2018.

4.Irwin K, Sexton C, Daniel T, et al. Healthy Aging and Dementia: Two Roads Diverging in Midlife? Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:275-.

5.Apostolo J, Holland C, O'Connell MD, et al. Mild cognitive decline. A position statement of the Cognitive Decline Group of the European Innovation Partnership for Active and Healthy Ageing (EIPAHA). Maturitas. 2016;83:83-93.

6.Campbell NL, Unverzagt F, LaMantia MA, et al. Risk factors for the progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):873-93.

7.Levy R. Aging-associated cognitive decline. Working Party of the International Psychogeriatric Association in collaboration with the World Health Organization. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6(1):63-8.

8.Snyder PJ, Jackson CE, Petersen RC, et al. Assessment of cognition in mild cognitive impairment: a comparative study. Alzheimers Dement.2011;7(3):338-55.

9.Pavlovic DM, Pavlovic AM. [Mild cognitive impairment]. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2009;137(7-8):434-9.

10.Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, et al. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):59-66.

11.Csukly G, Siraly E, Fodor Z, et al. The Differentiation of Amnestic Type MCI from the Non-Amnestic Types by Structural MRI. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:52.

12.Lawrence BJ, Gasson N, Loftus AM. Prevalence and Subtypes of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson's Disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33929.

13.Roberts R, Knopman DS. Classification and epidemiology of MCI. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):753-72.

14.Serrano CM, Dillon C, Leis A, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: risk of dementia according to subtypes. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2013;41(6):330-9.

15.Henderson VW. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Stanford ADRC

16.Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, et al. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(1):13-22.

17.Woods RT, Moniz-Cook E, Iliffe S, et al. Dementia: issues in early recognition and intervention in primary care. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(7):320-4.

18.Evans D, Price K, Meyer J. Home Alone With Dementia. SAGE Open. 2016;6(3):2158244016664954.

19.Brodaty H, Heffernan M, Kochan NA, et al. Mild cognitive impairment in a community sample: The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(3):310-7.e1.

20.Lilly MB, Robinson CA, Holtzman S, et al. Can we move beyond burden and burnout to support the health and wellness of family caregivers to persons with dementia? Evidence from British Columbia, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20(1):103-12.

21.Courtney DL. Dealing with mild cognitive impairment: help for patients and caregivers. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):895-905.

22.Snyder PJ, Jackson CE, Petersen RC, et al. Assessment of cognition in mild cognitive impairment: a comparative study. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):338-55.

23.Lilly M, Robinson C, Holtzman S, et al. Can we move beyond burden and burn-out to support the health and wellness of family caregivers to persons with dementia? evidence from British Columbia Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:103 - 12.

24.Haibo X, Shifu X, Pin NT, et al. Prevalence and severity of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Chinese: findings from the Shanghai three districts study. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(6):748-52.

25.Mendez Rubio M, Antonietti JP, Donati A, et al. Personality traits and behavioural and psychological symptoms in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;35(1-2):87-97.

26.Tible OP, Riese F, Savaskan E, et al. Best practice in the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2017;10(8):297-309.

27.Willis SL. Everyday cognitive competence in elderly persons: conceptual issues and empirical findings. Gerontologist. 1996;36(5):595-601.

28.Berezuk C, Ramirez J, Black SE, et al. Managing money matters: Managing finances is associated with functional independence in MCI. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(3):517-22.

29.Samus QM, Davis K, Willink A, et al. Comprehensive home-based care coordination for vulnerable elders with dementia: Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus-Study protocol. Int J Care Coord. 2017;20(4):123-34.

30.Clark A, Campbell S, Keady J, et al. Neighbourhoods as relational places for people living with dementia. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;252:112927.

31.Ward R, Clark A, Campbell S, et al. The lived neighborhood: understanding how people with dementia engage with their local environment. International psychogeriatrics. 2018;30(6):867-80.

32.Kukreja D, Günther U, Popp J. Delirium in the elderly: Current problems with increasing geriatric age. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142(6):655-62.

33.Davis DHJ, Muniz-Terrera G, Keage HAD, et al. Association of Delirium With Cognitive Decline in Late Life: A Neuropathologic Study of 3 Population-Based Cohort Studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):244-51.

34.Knopman DS, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: a clinical perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(10):1452-9.

35.Hedman A, Lindqvist E, Nygård L. How older adults with mild cognitive impairment relate to technology as part of present and future everyday life: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics. 2016;16(1):73.

36.Manera V, Petit P-D, Derreumaux A, et al. 'Kitchen and cooking,' a serious game for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:24-.

37.Evans IEM, Llewellyn DJ, Matthews FE, et al. Living alone and cognitive function in later life. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;81:222-33.

38.Drennan VM, Greenwood N, Cole L. Continence care for people with dementia at home. Nurs Times. 2014;110(9):19.

39.Dekkers W. Dwelling, house and home: towards a home-led perspective on dementia care. Med Health Care Philos. 2011;14(3):291-300.

40.Ward R, Clark A, Campbell S, et al. The lived neighborhood: understanding how people with dementia engage with their local environment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(6):867-80.

41.Grande G, Vetrano DL, Cova I, et al. Living Alone and Dementia Incidence: A Clinical-Based Study in People With Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(3):107-13.

42.Gibson AK, Richardson VE. Living Alone With Cognitive Impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32(1):56-62.

43.Faeo SE, Husebo BS, Bruvik FK, et al. "We live as good a life as we can, in the situation we're in" - the significance of the home as perceived by persons with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):158.

44.Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis2020.

45.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-73.

46.Streams ME, Wackerbarth SB, Maxwell A. Diagnosis-seeking at subspecialty memory clinics: trigger events. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(10):915-24.

47.Peterson K, Hahn H, Lee AJ, et al. In the Information Age, do dementia caregivers get the information they need? Semi-structured interviews to determine informal caregivers' education needs, barriers, and preferences. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):164.

Received: December 15, 2020;

Accepted:January 23, 2021;

Published: January 27, 2021 .

To cite this article : Perruchoud E,von Gunten A, Ferreira T, et al.Citizens, Neighbors, and Informal Caregivers Exposed to ChallengingBehaviors and Behavioral Changes in Community-Dwelling Older Adultswith Cognitive Impairment: A Review. Health Education and Public Health. 2021; 4:1.

©Perruchoud E.2021.