Research Article / Open Access

DOI: 10.31488/HEPH.173

Opportunities to Enhance Dental Education through Partnerships with Communities in Need

Van Tubergen E*, Kane L, Fitzgerald M, Hamerink H, Piskorwoski WA

1.Department of Cardiology, Restorative Sciences & Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Michigan, USA

*Corresponding author:Van Tubergen EA, Clinical Associate Professor, Dept. Cariology, Restorative Sciences & Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Michigan, 1011 N. University 1376F, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1078, USA, Tel: 734-647-6860

Abstract

The community based dental education program (CBDE) at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry (UMSoD) is diverse and robust and offers a unique clinical experience where students can improve their dental competence. In this article, we highlight the programs that are currently implemented while discussing the target populations for the sites, examine the types of dental experiences the fourth year dental students encounter at each location and discuss how dentists around the state of Michigan can get involved in the program. While a growing component at the UMSoD curriculum, the CBDE program has many benefits to training competent dental clinicians and reaching patients that may otherwise not have opportunities to seek dental treatment.

Introduction

Community based dental education (CBDE) programs create a unique clinical experience during dental training. Dental students are able to gain vast clinical experience and improve their clinical skills while treating patients in underserved areas. The University Of Michigan School Of Dentistry (UMSoD) has one of the most robust CBDE programs in the country. The CBDE model at the UMSoD allows students to treat patients at multiple locations throughout Michigan, which can include federally qualified health centers, Indian health services, correctional facilities, community clinics, dental service organizations, private practice opportunities and Selective Services Programs (SSP). This article will focus on detailing each of the CBDE models that are currently being utilized or in development at UMSoD. Overall, all of these CBDE models capitalize on existing dental opportunities within communities and cater to underserved populations and individuals that have limited access to care while focusing on giving students abundant opportunities to improve their clinical skills.

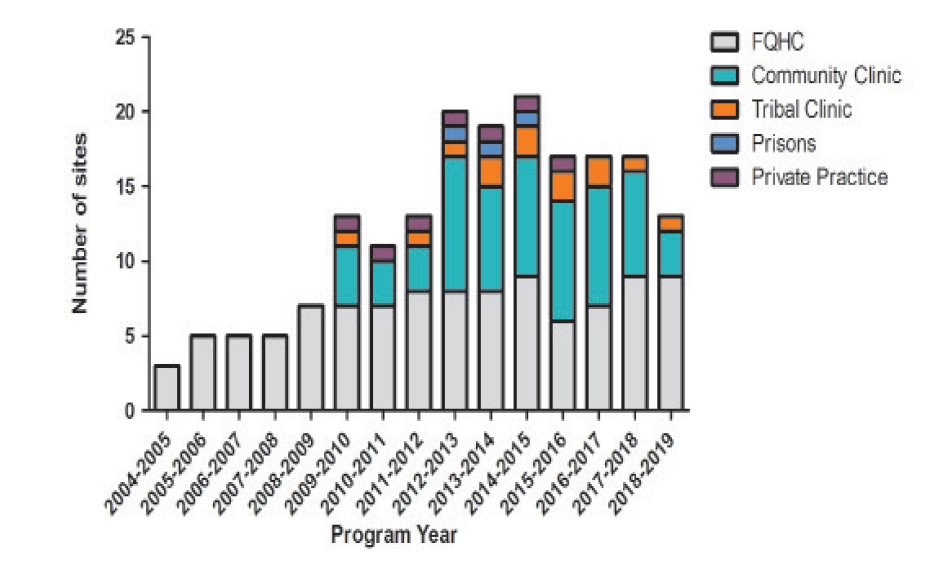

The CBDE program at the UMSoD started in the early 2000’s and included 3 weeks of external rotations within 5 different clinical sites. In total, the CBDE program has had 45 different site affiliations all over the state of Michigan as the CBDE program expanded at UMSoD from its inception in 2002 to the year 2016. This expansion can be viewed in figure 1. At the present time, fourth year dental students participate in nine weeks of external rotations at CBDE facilities around the state of Michigan at 15 different sites. The program will increase to 12 weeks in the foreseeable future. The programs depth and breadth increased dramatically over the years because of its popularity from students and need for access to care for residents of Michigan.

Figure1:Growth of CBDE program at UMSoD over a decade from 4 programs to over 20 during its inception.

Figure2:Locations across the state of Michigan that have affiliations with the UMSoD. Key - Orange Triangle: Community health Center. Red star: Federally qualified Health Center. Blue circle: Indian health center, Star: Heart: private practice model. Square: federal prison.

A benefit of the CBDE program is that dental students are able to complete required clinical competencies and reflective assignments based on their clinical experiences. Moreover, clinical skills are constantly improved at a pace that more reflects working in a private practice with a dental assistant as compared to learning in the dental school clinic. Students participating in these external rotation experiences feel that it improves their clinical skills and confidence [1]. Moreover, a study in 2007 identified that students could generate similar-revenue equivalents in half the time as students working in the school’s dental clinic [2]. Improvement in student’s clinical confidence and enhancing clinical productivity underscores the importance of the role CBDE programs play in dental education. It should be noted that prior to going on rotations, fourth year dental students have had numerous courses and patient centered interactions in social sciences that prepare them to interact with patients from all different socio-economic backgrounds. Moreover, while on rotations, students are not required to perform a specific number of procedures. All production by the students is based on the need of each individual patient.

A paradigm shift occurs in dental education with the development and implementation of CBDE programs. Firstly, dental institutions can address the needs of the students as they train to be dentists and become more confident clinicians based on feedback from site evaluations. Secondly, the schools can focus on treating patients that have numerous barriers to access to care. Lastly, CBDE programs in cooperation with their contracted sites can evolve in to profit sharing revenue for the schools [3]. Additionally, schools are able to develop and implement different outreach formats that target specific patient populations without access to dental care while also tailoring to the needs of the school and student. Moreover, programs can be created without interfering with the surrounding populations of graduated alumnae. A CBDE affiliation can be successfully implemented in areas just outside the dental school if there is a large enough diverse population of patients that are typically not targeted by graduates in private practice. The initial rationale for the development of the CBDE curriculums was to serve areas at or below 200% of the poverty level. This would target patients that have poor access to care and possess financial barriers. Local clinic affiliations in surrounding areas outside of a dental school will limit travel and housing expenses for any CBDE program. Additionally, depending on the need of a particular area a CBDE program could be specifically designed to target a specific patient population.

Below we will describe the rationale for each target site selected for affiliation with UMSoD CBDE program.

Locations

Federally qualified health center

One of the main target affiliations for the CBDE program at UMSoD are federally qualified health centers (FQHC). Barriers exist for impoverished individuals in both urban and rural locations to receive medical and dental treatment. Two such barriers to attaining dental treatment are access to care and the cost of dental treatment [4]. In order to address the need for access to comprehensive medical and dental care, the federal government opened (financed) federally qualified health centers to improve access to medical and dental care due to poor reimbursement of Medicaid and Medicare at traditional medical centers [5]. These outpatient medical facilities are funded with federal grant monies under section 330 of the Public Health Service Act. FQHCs target populations that are at or below 200% of the local poverty level. They do not limit treatment to those that fall above the poverty level, but these patients can pay based on a sliding fee for the area or at rates that are adjusted to the local area.

All FQHCs manage comprehensive medical care and oral health issues [6]. Dental services are provided at either an onsite dental clinic or on a referral to other locations. Given the scope of patients being seen at FQHCs, these centers provide numerous experiences for dental students while they are training to become dentists. In the state of Michigan, there are approximately 40 FQHCs and only 22 are able to provide dental care on site. While at a national level, around 1,131 (75%) FQHC facilities possessed onsite dental clinics in 2009 [7,8]. In the state of Michigan, in 2015 around 30% of FQHC patients were seen as dental patients [9]. The CBDE program at UMSoD has been involved with FQHCs since the inception of the program. Each of the FQHCs in the CBDE program is located all over the state of Michigan from rural northern Michigan to metro-Detroit. FQHC dental clinics are staffed by dentists and treat a wide variety of patients from simple restorations, extractions, prosthodontic care and periodontal therapy. Student involvement at these facilities enhances the number of patient visits at these facilities.

Tribal clinics

Another high priority affiliation site for the UMSoD CBDE program to become aligned with are the Indian Health Services (IHS) and tribal dental clinics. The IHS is an agency within the Federal Department of Health and Human Services and is responsible for improving health services to American Indians and Alaskan Natives. The overarching goal for the IHS is to be the principle federal health care provider and health advocate for indigenous peoples while raising their health status to the highest-level possible. The IHS provides health care services to over 2 million Native Americans on reservations, in rural communities and in urban areas [10]. IHS services are delivered in three ways: through direct (IHS) services; through tribal services; or by contract with non-IHS service providers with annual appropriations for IHS of over 6 billion in 2016 [11].

There are 11 hospital based dental tribal clinics, - 160 clinic-based dental clinics and 11 urban based dental clinics in the country that are regulated by two area offices. The state of Michigan is covered by the Bemidji area office [11]. This office manages 34 nationally recognized tribes and 4 urban Indian clinics and serves 136 million native individuals. There are 22 tribal clinics in Michigan, all of which are able to perform dental procedures [12]. The UMSoD has had up to two affiliations with tribal clinics in Brimley and Peshabestown. Both of these clinics offer a unique arrangement with the UMSoD because of their current funding mechanisms. Both sites function as a FQHC for the area, so they offer care to individuals beyond tribal members. The CBDE program for the University of Michigan has focused on building affiliations with these tribal clinics because of the funding mechanism to the tribal clinics compared to IHS dental clinics. While at these clinics, students get to perform a large variety of dental treatment consisting of but not limited to: routine exams, prophylaxis, sealants, root canal therapy, periodontal surgery, direct restorative procedures, removable and fixed prosthodontic services, minor orthodontic therapy and oral surgery procedures. The benefit of the arrangement with these tribal clinics is that students can treat a large number of patients with comprehensive dental care and be exposed to native cultures.

Correctional facilities

Another opportunity to target underserved populations for the CBDE program is to establish a program at state and local correctional facilities. There are currently 35 open prisons in the state of Michigan overseen by the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) [13] and operated under the direction of the Correctional Facilities Administration (CFA). Upon intake, all prisoners receive a comprehensive dental examination. Incarcerated inmates are provided routine and emergency dental treatment per MDOC policy directive 04.06.150 that is deemed necessary and requested by the inmate [14]. Treatment can include prophylaxis, oral surgery, amalgam and composite fillings, endodontics, and prosthetic services. Currently, at the Huron Valley Women’s Facility in Ypsilanti Michigan, there is a dental lab run by Michigan State Industries (MSI) where female prisoners fabricate conventional complete dentures, interim partial dentures, and occlusal guards for incarcerated prisoners. Students at the UMSoD CBDE program currently rotate through the Jackson and Ypsilanti correctional facilities from 1-3 week intervals providing these dental services. In discussion with both the students and the Dental Director Dr. Choi, these rotations are considered an invaluable clinical experience since many of the prisoners have never been to a dentist before and the amount of advanced dental disease seen is daunting.

Community clinics

Community or neighborhood clinics were originally established in the 1960’s under the “Economic Opportunity Act of 1964” in President Johnson’s war on poverty. Unlike FQHCs which are federally funded, community clinics are generally funded by the state. Community health centers/clinic can be a FQHC and the terms FQHC and community health clinic can be used interchangeably depending on the funding mechanisms. For the purposes of this paper, we are considering community dental clinics only those that receive funding from the state and/or local entities. Community clinics are locally run non-profit organizations in existence to service those with limited access to care (medically underserved area or population). Some community clinics are established by philanthropic contributions of foundations and other contributors; thus, they may be private or public entities. A board of people from the local community governs community clinics. The majority of these board members are seen as patients at the particular clinic [15]. Since the governing board members represent the population being served, the specific needs of the community can be better addressed than say someone governing from afar. The community health clinic model is used throughout the United States and the average number of clinics per state is 35. Michigan, the 8th largest state in the US has fewer than the average number of community clinics.

Community clinics are open to serve all members of the community whether they are insured or not. They have the ability to provide fee adjustments for the uninsured based on the individual’s ability to pay (sliding scale) [16]. The majority of patients treated at these clinics are adults and children on Medicaid (85%) with the rest being low-income uninsured persons whose income is below 200% of the poverty level. Unfortunately, the sliding fee schedule still results in patients not being able to afford dental treatment since this model works along the lines of low cost care and not free care. Michigan Community Dental Clinics (MCDC) are located throughout the state of Michigan and have had numerous site affiliations with the UMSoD CBDE program. Currently, the VINA community dental center of Livingston County is an example of a community outreach center UMSoD students rotate through. VINA, established in 2008, provides basic dental care to low-income and uninsured patients living in Livingston County, serving over 2,000 patients in the community that do not qualify for Medicaid. Treatment costs at this site are supplemented by donations from the local community and each appointment is a flat fee, but treatment options are limited to extractions, cleanings and routine dental fillings and interim dental prosthesis that are tooth retained and in an esthetic zone. The Hope Dental Clinic in Ypsilanti Michigan is another community clinic UMSoD CBDE site providing cleanings, fluoride treatments, sealants, fillings, and simple extractions. In 2014, the Hope Clinic provided 4,529 dental visits for 1,311 patients. Communities also have the ability to use state monies to rent or contract private practices to treat the needs the community. The Wolverine Patriot Project is one such program that uses a local dentist office and pays a per diem based on production to the office being used while treating local veterans in Northern Michigan. It should be noted that the Wolverine Patriot Project is not part of UMSoD CBDE program but is an elective Pathways program in the dental curriculum. It also reflects how communities can develop clinic models that fit the needs of their community.

Selective services program

A private practice model is the traditional model of patient centered dentistry. However, many private practices are limited to treating patients with private dental insurance or ones that have the means to pay out of pocket dental treatment fees. The CBDE program and UMSoD has found that private practice offices in many communities can offer many opportunities for CBDE programs to provide treatment to patients that have poor access to care and are at or below 200% of the poverty level. One example of the CBDE affiliate with the UMSoD is an office in the suburb of Detroit, Michigan. This office treats juvenile delinquents on the days that dental students are rotating through the office. These offices can serve as a pillar for the community to reach the underserved populations of any area and does not have to be limited to juvenile delinquents. Specifically, a niche for offices like this is to treat uninsured patients in a community that may or may not qualify for Medicaid. While this arm of the CBDE program has the smallest representation and also is an elective in the outreach program of the Pathways programs, it offers many opportunities to establish sites that treat patients that have many barriers accessing to dental care. For example, offices can have students rotate through their office to treat foster children, individuals from women shelters, homeless shelters and human trafficking victims.

An area of focus for the selective service programs is on veterans. Michigan has over 700,000 veterans and over 50,000 veterans lack permanent housing. Thus, the Wolverine Patriot Project was born and focuses on dental treatment of veterans in Northern Michigan. This model is successful because dentists volunteer in an office that treats only veterans. At this time the services performed are extractions, implants, removable prosthetics, restorative work and periodontics. The students are able to work with the calibrated adjunct faculty. Hundreds of patients received comprehensive dental care and it’s a very valuable experience for the students. One item that is different in this model for CBDE is that a reimbursement fee for the University of Michigan does not exist because of the fact that the services are donated.

Conclusions

Developing a CBDE program is feasible at many locations in targeted areas. At the UMSoD the site focus was to serve patient populations that have many barriers to access dental care and to target communities with large patient populations at 200% below the poverty line. The CBDE can be accountable with feedback from student evaluations and preceptor evaluations after each external site experience to be sure that the level of dentistry performed is exceptional and validated [17]. Additionally, these CBDE program should be self-sufficient with negotiated contracts to become a revenue generator for the dental school. Most importantly, the CBDE program improves access to care for Michiganders and expands the clinical competence of dental students.

References

1. Piskorowski WA, Stenafac SJ, Fitzgerald M, et al. Influence of community-based dental education on dental students' preparation and intent to treat underserved populations. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(5):534-539.

2. Bean CY, Rowland ML, Soller H, et al. Comparing fourth-year dental student productivity and experiences in a dental school with community-based clinical education. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(8):1020-1026.

3. Piskorowski W, Bailit HL, McGowan TL, et al. Dental school and community clinic financial arrangements. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(10 Suppl):S42-47.

4. Vujicic M, Yarbrough C, Nasseh K. The effect of the Affordable Care Act's expanded coverage policy on access to dental care. Med Care. 2014;52(8):715-719.

5. Goebel J. A Brief History of Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC). 2013; https://www.notifymd.com/a-brief-history-of-federally-qualified-health-centers-fqhc/.

6. EJ H. Federal health centers: an overview. In. Washington (DC): Congresionsal Reserach Service; 2015.

7. Bureau of Primary Health Care program information notice. In:2003.

8. CureMD. Frequently Asked Questions about Federally Qualified Health Centers and their Oral Health Programs. 2009; https://www.curemd.com/cure_pdf_file/FQHC FAQs.pdf.

9. The Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Federally QUalified Health Centers in Michigan. University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, MI; 2016. Accessed September 2016.

10. Overview of the Indian Health Service Program. In: serviced Dohah, ed. online1994.

11. HHS FY2016 Budget in Brief. In: Services DoHaH, ed2016.

12. In: Affairs DoV, ed. Federal Health Care Facilities 2017.

13. Prisons. In: Corrections MDo, ed2017.

14. Michigan So. Department of Corrections. 2017; http://www.michigan.gov/corrections/0,4551,7-119-68854_1381_1385---,00.html. Accessed 09.05.2017, 2017.

15. Frey C. Community Health Centers: In the Beginning. Alliance for Rural Community Health. California Primary Care Association. 2015.

16. Centers NAoCH. Module 1: An Introduction To The Community Health Center Model. In:2017.

17. Ramaswamy V, Piskorowski W, Fitzgerald M, et al. Psychometric Evaluation of a 13-Point Measure of Students' Overall Competence in Community-Based Dental Education Programs. J Dent Educ. 2016;80(10):1237-1244.

Received: January 17, 2022;

Accepted: February 14, 2022;

Published: February 17, 2022.

To cite this article : Van Tubergen EA, Kane L, Fitzgerald M, et al. Opportunities to Enhance Dental Education through Partnerships with Communities in Need. Health Education and Public Health. 2022; 5(1): 471-476. doi: 10.31488/HEPH.173.

© 2022 Van Tubergen EA, et al.